—

To begin, when did you first start painting, and how did you come to create this series? What are its ideological origins or artistic influences?

I started painting at a very young age, somewhere around 10–12 years old. I believe at that time I knew I wanted to be an artist, or rather, that I had to be an artist.

If there is an ideology it is awareness through creativity. Very early on I was obsessed with perception and how we make sense of the world. I gravitated toward painting and drawing because they can be quite fast, and you don’t need a lot of equipment or materials. I also really like that painting is a solitary activity. It’s easier for me to channel ideas and forms when I’m alone and quiet. Growing up in the Southwest I didn’t have access to contemporary art. I spent a lot of time in the library and found that artists like Cézanne and Mondrian left road maps to how they made paintings. Mexican and Native American arts and crafts also influenced me; especially magical realism and things of spiritual nature.

— You make use of both acrylic paint and synthetic polymers in your works to wonderful effect—there is an especially other-worldly quality to the soft areas of color that seem to echo or reflect more starkly delineated geometric forms. Can you describe your process of creating these compositions?

My process can be described in three very distinct parts:

First there is concept

Then there is channeling

And finally there is tuning.

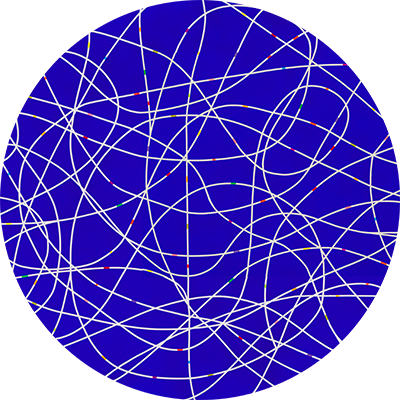

— One of the joys of your work is how it evokes both the ‘primitive,’ or prehistoric, and the futuristic. The block of purple, blue, red, and yellow rectangles that appears in nearly every painting (especially when set against the landscape-like black fields of Ascension Projection and Untitled (Spectre)), reminds me of the mysterious monolith in 2001 A Space Odyssey, which is sent to a group of hominids from an alien race in the future. This monolith is the blueprint, in a sense, for the various refractions of color that take place across your canvases. The loops and zigzags of Groundwater and Origin #3, for example, call to mind a kind of abstract map or info-graphic, while the shapes (or symbols?) of Spectra Informa speak to both the mark-making of early humans and the output of computers, like a chromatic dataset. (I see a bit of HAL, the super-computer in 2001, in works like Origin 2, as well). A set of questions emerges from this comparison: First, out of curiosity, are you a fan of Kubrick? Is this relationship between the past and future something that you feel guides your artistic inquiry? And finally, what role, if any, does data or technology play into your paintings?

I’m a big fan of Kubrick. He has such a wonderful visual delivery. The films are intelligent on a whole other level. I wish there were more of them. The monolith in 2001 is a fascinating character to me. I believe there are similar monuments in ancient civilizations but with writing on them. Kubrick just took off any symbols or markings, and voilà it’s alien. I’m very interested in how this negation of expectation can lead to the mysterious.

Almost all of the recent paintings start with some kind of abstracted phenomenological event, and then I add a small spectral entity that is experiencing the event. I often ground the painting with a symbolic picture structure such as horizon line or sky. The events are out of time but very much in space. Time is just relative to the observer so the paintings jump around through visual history. To be honest, I’m just trying to paint what it feels like to be alive with some sort of awareness. What we perceive with our senses is just a tiny fraction of reality so there is a lot of room for imagination and invention. I’ve always thought of myself as a prism reflecting and refracting my environment. My awareness comes and goes like the focus on a camera. We live in an incredibly complex moment where our technology requires us to lose our focus (awareness) just to participate in society. It’s very strange and disorienting. Sometimes when I’m painting I imagine what would happen if AI took on the more absurd human qualities. For example, what would happen if AI fell deeply and romantically in love with nature?

— In a similar vein, do you draw inspiration from literature and other art forms in your life and work? Does language figure into your practice at all?

Yes, absolutely. I adore Borges and Stanislaw Lem. They both ride a fine line between abstraction and representation, and that is something I try to do in my work. I also feel very connected to concrete poetry. Mary Ellen Solt and Aram Saroyan have had an influence, but I found out about them much later in my artistic life. I have written poetry for most of my adult years, and it has always been in the vein of concrete poetry, even before I knew what that was. It’s part of the way I process things. Words are like colors to me; they mean nothing, they mean everything.

— In poetry, it often feels as though a composition is never complete; I sometimes find myself tinkering with lines and words years after I’ve ‘finished’ composing a poem. Do you find that the same is true in painting? How do you know when you are done?

I definitely find that true in painting. An artwork comes into existence when it needs to. We just shepherd it into reality. I have worked on things for years and sometimes decades. A lot of the time I’m just looking for the right form for an idea. I don’t always edit the false starts. The search is part of being human.

— Where would you like to take this series next? Or have you begun working on a different project?

There is still a lot to investigate in this series and I’m excited to expand upon what I’ve started. In the studio I always have a few different series going on simultaneously. There is a group of text paintings that I’ve been developing over the last few years. I’m hoping to get closer to resolving some of them soon.

The older I get the more important it has become to live my life like an artwork. I’ve spent most of the summer hiking the trails of upstate New York. I feel like that has been extremely productive even if there is no immediate output. When you’re really quiet and patient in the mountains, the rocks and trees tell you who they are, and their names are vast and beautiful.

I started painting at a very young age, somewhere around 10–12 years old. I believe at that time I knew I wanted to be an artist, or rather, that I had to be an artist.

If there is an ideology it is awareness through creativity. Very early on I was obsessed with perception and how we make sense of the world. I gravitated toward painting and drawing because they can be quite fast, and you don’t need a lot of equipment or materials. I also really like that painting is a solitary activity. It’s easier for me to channel ideas and forms when I’m alone and quiet. Growing up in the Southwest I didn’t have access to contemporary art. I spent a lot of time in the library and found that artists like Cézanne and Mondrian left road maps to how they made paintings. Mexican and Native American arts and crafts also influenced me; especially magical realism and things of spiritual nature.

— You make use of both acrylic paint and synthetic polymers in your works to wonderful effect—there is an especially other-worldly quality to the soft areas of color that seem to echo or reflect more starkly delineated geometric forms. Can you describe your process of creating these compositions?

My process can be described in three very distinct parts:

First there is concept

Then there is channeling

And finally there is tuning.

— One of the joys of your work is how it evokes both the ‘primitive,’ or prehistoric, and the futuristic. The block of purple, blue, red, and yellow rectangles that appears in nearly every painting (especially when set against the landscape-like black fields of Ascension Projection and Untitled (Spectre)), reminds me of the mysterious monolith in 2001 A Space Odyssey, which is sent to a group of hominids from an alien race in the future. This monolith is the blueprint, in a sense, for the various refractions of color that take place across your canvases. The loops and zigzags of Groundwater and Origin #3, for example, call to mind a kind of abstract map or info-graphic, while the shapes (or symbols?) of Spectra Informa speak to both the mark-making of early humans and the output of computers, like a chromatic dataset. (I see a bit of HAL, the super-computer in 2001, in works like Origin 2, as well). A set of questions emerges from this comparison: First, out of curiosity, are you a fan of Kubrick? Is this relationship between the past and future something that you feel guides your artistic inquiry? And finally, what role, if any, does data or technology play into your paintings?

I’m a big fan of Kubrick. He has such a wonderful visual delivery. The films are intelligent on a whole other level. I wish there were more of them. The monolith in 2001 is a fascinating character to me. I believe there are similar monuments in ancient civilizations but with writing on them. Kubrick just took off any symbols or markings, and voilà it’s alien. I’m very interested in how this negation of expectation can lead to the mysterious.

Almost all of the recent paintings start with some kind of abstracted phenomenological event, and then I add a small spectral entity that is experiencing the event. I often ground the painting with a symbolic picture structure such as horizon line or sky. The events are out of time but very much in space. Time is just relative to the observer so the paintings jump around through visual history. To be honest, I’m just trying to paint what it feels like to be alive with some sort of awareness. What we perceive with our senses is just a tiny fraction of reality so there is a lot of room for imagination and invention. I’ve always thought of myself as a prism reflecting and refracting my environment. My awareness comes and goes like the focus on a camera. We live in an incredibly complex moment where our technology requires us to lose our focus (awareness) just to participate in society. It’s very strange and disorienting. Sometimes when I’m painting I imagine what would happen if AI took on the more absurd human qualities. For example, what would happen if AI fell deeply and romantically in love with nature?

— In a similar vein, do you draw inspiration from literature and other art forms in your life and work? Does language figure into your practice at all?

Yes, absolutely. I adore Borges and Stanislaw Lem. They both ride a fine line between abstraction and representation, and that is something I try to do in my work. I also feel very connected to concrete poetry. Mary Ellen Solt and Aram Saroyan have had an influence, but I found out about them much later in my artistic life. I have written poetry for most of my adult years, and it has always been in the vein of concrete poetry, even before I knew what that was. It’s part of the way I process things. Words are like colors to me; they mean nothing, they mean everything.

— In poetry, it often feels as though a composition is never complete; I sometimes find myself tinkering with lines and words years after I’ve ‘finished’ composing a poem. Do you find that the same is true in painting? How do you know when you are done?

I definitely find that true in painting. An artwork comes into existence when it needs to. We just shepherd it into reality. I have worked on things for years and sometimes decades. A lot of the time I’m just looking for the right form for an idea. I don’t always edit the false starts. The search is part of being human.

— Where would you like to take this series next? Or have you begun working on a different project?

There is still a lot to investigate in this series and I’m excited to expand upon what I’ve started. In the studio I always have a few different series going on simultaneously. There is a group of text paintings that I’ve been developing over the last few years. I’m hoping to get closer to resolving some of them soon.

The older I get the more important it has become to live my life like an artwork. I’ve spent most of the summer hiking the trails of upstate New York. I feel like that has been extremely productive even if there is no immediate output. When you’re really quiet and patient in the mountains, the rocks and trees tell you who they are, and their names are vast and beautiful.

Adam Henry was interviewed by Madeline Gilmore via email, October 2024.

©2026 Volume Poetry