Chime Lama was interviewed over email in May 2024 by Madeline Gilmore.

— I thought we could start with your poem "Classic Letter," which opens this issue of Volume and also opens your debut poetry collection, Sphinxlike. In the book, after an announcement to the owner of a parked golden 1963 PeelP50, the colophon page, and a table of contents that twists and turns with lines and titles like an amped-up game of connect the dots, "Classic Letter" appears to float weightless on the page. I love the sense of calm and mystery that emanates from it. Can you talk a bit about this poem? What does this letter 'represent?'

"Classic Letter" was the catalyst for this entire collection. I created it, quite curiously, years before I began writing poetry and something about it stuck with me. I would look at it and think, “Yes. I like that. I want to do that (whatever that is).” It was my first Tibetan-English concrete poem that would serve as my north star as I continued to engage with poetry more seriously.

The poem “Classic Letter” has no letters and is composed of punctuation. It contains the English semicolon that expresses a serious pause, but not an end, the English parenthesis that is used to enclose a secret or minor message, and the Tibetan ang khang[1] or “word house” that functions as brackets to highlight or feature whatever they contain.

These symbols are silent expressions not existing in the other’s language. They are used as tools to help the reader better understand the message that is being relayed by words. Contrary to this usage, in this poem, we see the semicolon, parentheses, and ang khang in the forefront as the central and only components of the poem.

One might ask, “How does one read this poem? Whatever does it mean?”

I, for one, find this refreshing. However, I’m aware that it may also be found perplexing. To witness language attempting to relay a meaning without a message presents us with a puzzle. It’s my hope that this puzzle beckons us to play.

The call-to-play is a repeating refrain within this collection: it asks of the reader to become a co-creator of the meaning they wish to receive. To bravely move from a passive to active agent. I liken this to hearing one’s childhood neighbor tapping at their window—will they answer the call?

As the creator, I hesitate to propose what “Classic Letter” might represent. However, when Dr. Shelly Bhoil presented on this poem at the international conference Charting the Uncharted World of Tibetan Women Writers Today (Paris, 2023), she noted how this bilingual poem puts two cultures and languages into conversation, which is also something forced upon Tibetans by exile and living in diaspora.

Dr. Bhoil elucidates upon the significance of the semicolon, mapping how it has

“…morphed from a simple punctuation mark to become an important signifier of survival in recent years. As mentioned on the website of Project Semicolon, a nonprofit movement founded in 2013 by Amy Bleuel to honor her father, who took his own life, and to give voice to her own fight with mental illness: ‘A semicolon is used when an author could’ve chosen to end their sentence but chose not to. The author is you, and the sentence is your life.’ Chime Lama’s concrete poem ‘Classic Letter’ could be carrying a message of affirmation and solidarity with Tibetans living between cultures and uncertainties and who have dealt with suicide, depression, and other mental health issues. It would urge readers, including Tibetan readers, to pause and embrace the symbol as a reminder that their story is not yet over, their story must be told.”[2]

I greatly appreciate this interpretation. That being said, I maintain that the reader is free to interpret the poem anyway she likes.

— One of the great joys of your collection is the happy surprise of different styles co-existing: There are poems composed on the typewriter, poems that radiate into different shapes, poems that are folded, poems that are collages, and much more. How do you think about form when you're writing? Does the subject matter inform the shape, or vice versa?

I think that each poem has its optimum form. It may take some time for me to intuit what that is, and it may require a fair amount of tinkering: turning, curving, moving, sizing, etc. However, when I’ve got it, I feel that I’ve nailed it, or something close to nailing it.

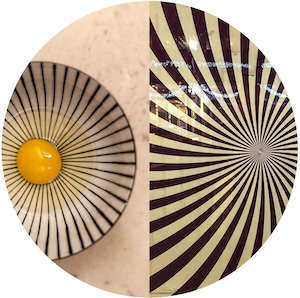

Yes, I believe that the subject matter does inform the shape. The emotion drives the movement of the words and is reflected in scale. Something that feels massive would naturally assume a massive form. Something that feels dismal may spiral heedlessly.

Once I have an idea of a poem and perhaps a rough draft (typed or drawn), I decide on how to create it: using computer software, a typewriter, a scanner or otherwise. I think each of these mediums has its own flavor, its own personality, and it’s my job to determine which medium suits which poem.

— Throughout all of your poetry, I glean a wonderful sense of humor and discovery, but also wisdom. (One of the lines in Spinxlike that has really stuck with me: "All my pursuits have been selfish.") "Fore/Back" is a perfect example, where the repetition of the causality formula (Since ______, then _______) begins to transcend the logic of a linear narrative. This poem toggles ceaselessly between the future and the past, the sentences curling around themselves in a kind of loop-logic that doesn't allow for the existence of one without the other. Does this feel true to your experience of the poem, or of your poetry more generally? How does time function in your work?

I’d like time to be irrelevant. It appears I have incidentally and overwhelmingly omitted refences to factual events in time in this collection. At times, doing so (including factual events in my poems) gives me a feeling of being weighed down or getting lost in the details, especially in terms of poetry. Time and place can be very relevant and significant in non-fiction writing. However, I find myself far less tethered to “the facts” and “time” when writing poetry. I do like the feeling of being in a timeless, weightless space that allows for limitless possibilities and manifestations. For me, poetry is a space where anything can happen.

— What about space? It's harder to do with a desktop, but with a mobile screen or in Spinxlike, you can follow the curves of "Refractions" by physically turning it, and this is true of a lot of your work in the collection. It creates a very distinct experience of reading!

I try not to take things for granted. I like questioning the framework, including norms of textual appearance. With design software, modifications can be easily made. However, I am disappointed with myself for not being adventurous enough in terms of the greater medium. While I value and appreciate the functionality of the book, I have an urge to break away from it. For my first final project during my MFA program at Brooklyn College, I handed Professor Berrigan a scroll. I managed to make my portfolio vertically legible and arguably comprehensible, rolling it up to fit inside a tubular incense container. I’m still proud of myself for that. I never did that again. I caved to convenience. I’ve been working on spiral poems that I really want to see as multifaceted inter-locking mobiles, smoothly spinning, suspended in air. This would require me to finagle with my printer, get out scissors and ideally a laminator, string… Clearly, my own laziness is the obstacle. I hope the desire to create alternative-medium poems will continue to mount until I do something about it. As you mentioned, I have a feeling that these types of poems would offer an exceedingly distinct experience to the reader.

— How long have you been writing poetry? Which poets or writers inspire and influence you?

Hmm, it depends on how you look at it. Poetry proper – maybe since 2018, 2017? But, I’ve been writing songs since I was thirteen or even younger. The habit of recording my thoughts as fodder for future creative writing has been engrained for decades. The attempt to crystalize a thought so that it can be clearly relayed is a project I have long deemed worthy. I think these practices continue to serve me in writing poetry.

I’m inspired by Susan Howe’s experimentation with fragmentation and illegibility, and her commitment to its precise performance.[3] She shows me how to be dedicated to the work.

I’m inspired by Douglas Kearney’s performative typography, brimming with life, and the energy he brings to his readings that are far more than readings.

I’m inspired by Sawako Nakayasu’s courageously interweaving Japanese with English as she sees fit, diverging from the custom of presenting one with the other neatly nearby and thereby allowing the reader to have the experience of unknowing. I also applaud her mediations on translation as art.

— Any final words for our readers?

I might suggest approaching Sphinxlike with an open mind and all one’s senses.

Oh, and as a cave dwelling yogi once uttered, “Relax.”

— I thought we could start with your poem "Classic Letter," which opens this issue of Volume and also opens your debut poetry collection, Sphinxlike. In the book, after an announcement to the owner of a parked golden 1963 PeelP50, the colophon page, and a table of contents that twists and turns with lines and titles like an amped-up game of connect the dots, "Classic Letter" appears to float weightless on the page. I love the sense of calm and mystery that emanates from it. Can you talk a bit about this poem? What does this letter 'represent?'

"Classic Letter" was the catalyst for this entire collection. I created it, quite curiously, years before I began writing poetry and something about it stuck with me. I would look at it and think, “Yes. I like that. I want to do that (whatever that is).” It was my first Tibetan-English concrete poem that would serve as my north star as I continued to engage with poetry more seriously.

The poem “Classic Letter” has no letters and is composed of punctuation. It contains the English semicolon that expresses a serious pause, but not an end, the English parenthesis that is used to enclose a secret or minor message, and the Tibetan ang khang[1] or “word house” that functions as brackets to highlight or feature whatever they contain.

These symbols are silent expressions not existing in the other’s language. They are used as tools to help the reader better understand the message that is being relayed by words. Contrary to this usage, in this poem, we see the semicolon, parentheses, and ang khang in the forefront as the central and only components of the poem.

One might ask, “How does one read this poem? Whatever does it mean?”

I, for one, find this refreshing. However, I’m aware that it may also be found perplexing. To witness language attempting to relay a meaning without a message presents us with a puzzle. It’s my hope that this puzzle beckons us to play.

The call-to-play is a repeating refrain within this collection: it asks of the reader to become a co-creator of the meaning they wish to receive. To bravely move from a passive to active agent. I liken this to hearing one’s childhood neighbor tapping at their window—will they answer the call?

As the creator, I hesitate to propose what “Classic Letter” might represent. However, when Dr. Shelly Bhoil presented on this poem at the international conference Charting the Uncharted World of Tibetan Women Writers Today (Paris, 2023), she noted how this bilingual poem puts two cultures and languages into conversation, which is also something forced upon Tibetans by exile and living in diaspora.

Dr. Bhoil elucidates upon the significance of the semicolon, mapping how it has

“…morphed from a simple punctuation mark to become an important signifier of survival in recent years. As mentioned on the website of Project Semicolon, a nonprofit movement founded in 2013 by Amy Bleuel to honor her father, who took his own life, and to give voice to her own fight with mental illness: ‘A semicolon is used when an author could’ve chosen to end their sentence but chose not to. The author is you, and the sentence is your life.’ Chime Lama’s concrete poem ‘Classic Letter’ could be carrying a message of affirmation and solidarity with Tibetans living between cultures and uncertainties and who have dealt with suicide, depression, and other mental health issues. It would urge readers, including Tibetan readers, to pause and embrace the symbol as a reminder that their story is not yet over, their story must be told.”[2]

I greatly appreciate this interpretation. That being said, I maintain that the reader is free to interpret the poem anyway she likes.

— One of the great joys of your collection is the happy surprise of different styles co-existing: There are poems composed on the typewriter, poems that radiate into different shapes, poems that are folded, poems that are collages, and much more. How do you think about form when you're writing? Does the subject matter inform the shape, or vice versa?

I think that each poem has its optimum form. It may take some time for me to intuit what that is, and it may require a fair amount of tinkering: turning, curving, moving, sizing, etc. However, when I’ve got it, I feel that I’ve nailed it, or something close to nailing it.

Yes, I believe that the subject matter does inform the shape. The emotion drives the movement of the words and is reflected in scale. Something that feels massive would naturally assume a massive form. Something that feels dismal may spiral heedlessly.

Once I have an idea of a poem and perhaps a rough draft (typed or drawn), I decide on how to create it: using computer software, a typewriter, a scanner or otherwise. I think each of these mediums has its own flavor, its own personality, and it’s my job to determine which medium suits which poem.

— Throughout all of your poetry, I glean a wonderful sense of humor and discovery, but also wisdom. (One of the lines in Spinxlike that has really stuck with me: "All my pursuits have been selfish.") "Fore/Back" is a perfect example, where the repetition of the causality formula (Since ______, then _______) begins to transcend the logic of a linear narrative. This poem toggles ceaselessly between the future and the past, the sentences curling around themselves in a kind of loop-logic that doesn't allow for the existence of one without the other. Does this feel true to your experience of the poem, or of your poetry more generally? How does time function in your work?

I’d like time to be irrelevant. It appears I have incidentally and overwhelmingly omitted refences to factual events in time in this collection. At times, doing so (including factual events in my poems) gives me a feeling of being weighed down or getting lost in the details, especially in terms of poetry. Time and place can be very relevant and significant in non-fiction writing. However, I find myself far less tethered to “the facts” and “time” when writing poetry. I do like the feeling of being in a timeless, weightless space that allows for limitless possibilities and manifestations. For me, poetry is a space where anything can happen.

— What about space? It's harder to do with a desktop, but with a mobile screen or in Spinxlike, you can follow the curves of "Refractions" by physically turning it, and this is true of a lot of your work in the collection. It creates a very distinct experience of reading!

I try not to take things for granted. I like questioning the framework, including norms of textual appearance. With design software, modifications can be easily made. However, I am disappointed with myself for not being adventurous enough in terms of the greater medium. While I value and appreciate the functionality of the book, I have an urge to break away from it. For my first final project during my MFA program at Brooklyn College, I handed Professor Berrigan a scroll. I managed to make my portfolio vertically legible and arguably comprehensible, rolling it up to fit inside a tubular incense container. I’m still proud of myself for that. I never did that again. I caved to convenience. I’ve been working on spiral poems that I really want to see as multifaceted inter-locking mobiles, smoothly spinning, suspended in air. This would require me to finagle with my printer, get out scissors and ideally a laminator, string… Clearly, my own laziness is the obstacle. I hope the desire to create alternative-medium poems will continue to mount until I do something about it. As you mentioned, I have a feeling that these types of poems would offer an exceedingly distinct experience to the reader.

— How long have you been writing poetry? Which poets or writers inspire and influence you?

Hmm, it depends on how you look at it. Poetry proper – maybe since 2018, 2017? But, I’ve been writing songs since I was thirteen or even younger. The habit of recording my thoughts as fodder for future creative writing has been engrained for decades. The attempt to crystalize a thought so that it can be clearly relayed is a project I have long deemed worthy. I think these practices continue to serve me in writing poetry.

I’m inspired by Susan Howe’s experimentation with fragmentation and illegibility, and her commitment to its precise performance.[3] She shows me how to be dedicated to the work.

I’m inspired by Douglas Kearney’s performative typography, brimming with life, and the energy he brings to his readings that are far more than readings.

I’m inspired by Sawako Nakayasu’s courageously interweaving Japanese with English as she sees fit, diverging from the custom of presenting one with the other neatly nearby and thereby allowing the reader to have the experience of unknowing. I also applaud her mediations on translation as art.

— Any final words for our readers?

I might suggest approaching Sphinxlike with an open mind and all one’s senses.

Oh, and as a cave dwelling yogi once uttered, “Relax.”

[1] In Sphinxlike this Tibetan punctuation is referred to as u-gur or “title tent.”

[2] Taken from Dr. Bhoil’s conference presentation, “Standing Strong in Blood and Cramps: A Discussion on Exile Tibetan Women’s Poetry in English." Courtesy Dr. Bhoil.

[3] See Howe performing Frolic Architecture with David Grubbs.

Chime Lama (འཆི་མེད་ཆོས་སྒྲོན།) is a Tibetan American writer, translator, and multi-genre artist based in New York. She serves as an Associate Editor of Yeshe Journal, and her work has been anthologized in The Penguin Book of Modern Tibetan Essays and Longing to Awaken: Buddhist Devotion in Tibetan Poetry and Song. Her poetry collection, Sphinxlike, is out now with Finishing Line Press. She lives with her husband and daughter in Rochester, NY, where she has taught Creative Writing at the Rochester Institute of Technology and St. John Fisher University.

[2] Taken from Dr. Bhoil’s conference presentation, “Standing Strong in Blood and Cramps: A Discussion on Exile Tibetan Women’s Poetry in English." Courtesy Dr. Bhoil.

[3] See Howe performing Frolic Architecture with David Grubbs.

Chime Lama (འཆི་མེད་ཆོས་སྒྲོན།) is a Tibetan American writer, translator, and multi-genre artist based in New York. She serves as an Associate Editor of Yeshe Journal, and her work has been anthologized in The Penguin Book of Modern Tibetan Essays and Longing to Awaken: Buddhist Devotion in Tibetan Poetry and Song. Her poetry collection, Sphinxlike, is out now with Finishing Line Press. She lives with her husband and daughter in Rochester, NY, where she has taught Creative Writing at the Rochester Institute of Technology and St. John Fisher University.

©2026 Volume Poetry