––

Thank you for taking the time to speak with Volume. You

continue to be a source of inspiration and understanding when it comes to

shaping my poetic world, and I know the same is true for so many others. I

think I have to begin with an unavoidable question: how have you spent the past

few months? Have you found that the pandemic has impacted your writing?

Well, Emily, I have to say at the start that you––your poems, your engagements with language, your imagination––continue to be an inspiration to me, even though it’s been a few years since we worked together at UVA when you were an undergraduate in our poetry honors program, the Area Program in Poetry Writing (APPW). I hope, too, that you and yours are keeping well.

One thing I’ve valued in the past few months is hearing about new projects and adventures, like the formation of Volume, for example, which are community-building and forward-looking at a time that can feel so stalled and horizon-less for many. At a time not only of plague-related and racial roil, but also in which some of the high-end publishing organizations are taking huge hits, the start of a fresh new venue for voices gives me hope. Even joy. “Volume” is a great title for a journal, by the way. It works on so many levels––not only the obvious denotation of a publication, but also in terms of physics (capacity, mass, heft, substance) and also sound––a sense of voices being heard in a range of pitches.

Because I direct two programs (both our MFA program and the APPW mentioned before) and serve on university committees, as well as teach classes at my university, I really didn’t get the “break” that sometimes happens for academics in the summer months. With my cohort of administrators, I just Zoomed on through May, June, July, and August, attempting to come up, collectively and individually, with ways to continue to teach higher education, whether in-person, online, or in some hybrid form, in a meaningful way. As someone said, it’s like flying an airplane while trying to build it.

Nonetheless, I have managed this past month (August) to read a few books for pleasure and to write some poems, essays, and reviews. One thing I did, at the request of some of the APPW poetry alumni last March, is to send out bi-weekly poetry prompts to the 180-some graduates (and current students) of the APPW. It was a way, not only for actively practicing poets, but perhaps especially for doctors, accountants, lawyers, mothers and fathers and other alumni of the program whose lives don’t ordinarily allow time for writing, people who suddenly found themselves working at their kitchen tables and with a different kind of time on their hands––to return to the making of poems. We did this from March through July and the result, collectively, is an extraordinarily moving, shared account of life and language in the time of pandemic. We took a hiatus in August, but I expect we’ll resume this fall. Connecting again with students from nearly twenty years ago, as well as those just admitted to the program, was incredibly sustaining for me during the first five months of the COVID pandemic. It reminded me why all the Zooming and other onerous challenges of trying to teach virtually––in a way that mattered––was worth it.

As a footnote: I’ll add that I have two new grandbabies––my first grandchildren––each conceived before the pandemic really hit, both due before the end of 2020. Not twins––different sets of parents. It’s a complicated time to start a family, but as the poet Charles Wright, a friend and former colleague, quipped when I told him the news: “It always is, Lisa, it always is.” Anticipating the arrival of these two new humans has been a source of hope during this hard time.

–– The poetry prompts you mention were also a pre-pandemic mainstay of your work within UVA's poetry program. Reading the three prompts you generously created for Volume, it strikes me that they are perhaps a means of “hoodwinking” poets into writing differently––of surprising them into remembering that language is always also a game and puzzle. I'm curious: do you have any specific criteria in mind, when devising a prompt? And how would you describe the place that prompts occupy in your own writing life? Are they a regular part of your practice, or are they more a tool to ease feelings of stuck-ness, of writer’s block?

I’m glad and grateful to have this opportunity to think about the genesis of “obstructions” or prompts in my own writing praxis and in my teaching. (Have you seen the Lars Von Trier movie The Five Obstructions, by the way? It’s very much a movie for poets, and for touting the ways in which art loves limits, and transcends them).

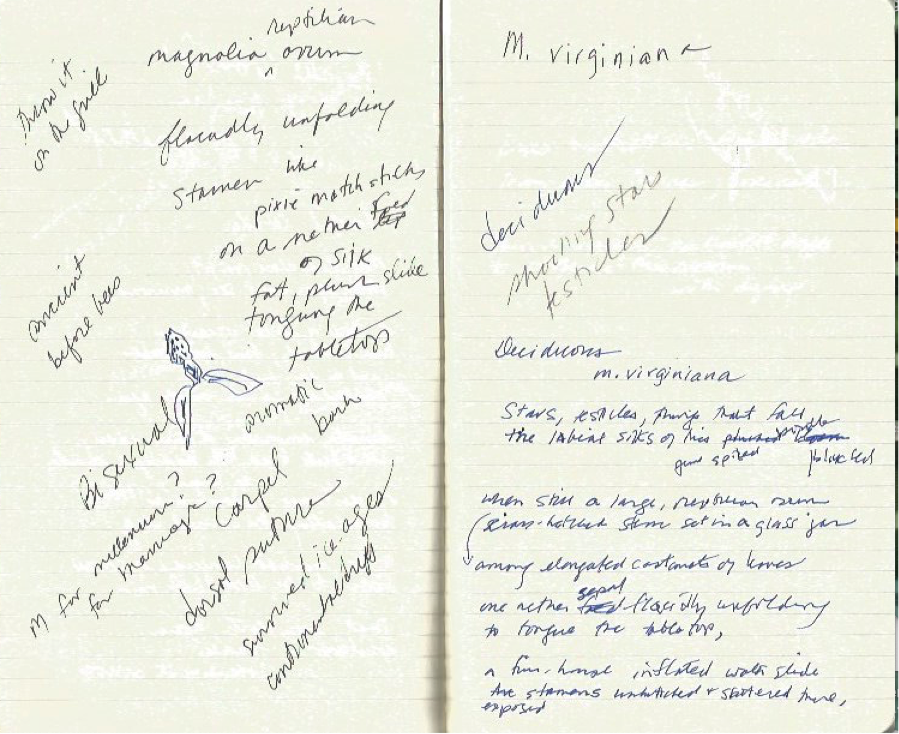

I think the beginnings of the value of being pitched something to resist as I write goes back to graduate school, when I was teaching and working a couple of other jobs while also trying to write poems. When I would get stuck on a given poem, or was stalled in a spell of writer’s block, I’d ask my husband to give me three or four randomly chosen words, and I’d use them to start a poem, looking up definitions, etymologies. In fact, I’m very much a word person, and often, most of the time, in fact, my poems begin with words that catch my interest (a word is of course itself a kind of poem, full of story, history, sonic rooms and eddies). If no one was around to pitch me words, I’d close my eyes and point randomly in the dictionary to find them (I have dictionaries in most of the rooms in my house––real ones, with letter tabs and illustrations). I still work this way, and I’ll try to insert a screen shot later of a page or two from my notebooks, where I start listing words or even little drawings on the verso (left page in a bi-fold notebook) and then start building the poem on the recto page, where at a certain point I move to the computer for finishing the draft and revising.

I use prompts with emerging and advanced students. For the former, it often helps an incipient poet by providing something with which to begin, rather than trying to conjure a poem out of nowhere (or with a break-up or Jesus). With advanced students, who are beginning to know their way around their own poems, it often forces the writer out of their comfort zone. Having something to bump up against, to try to work into a piece or, finally, resist, almost always yields not the “answer” to the assignment, but the poem the poet NEEDS to write. And that’s always the point of the prompts: not to fulfill all (or any) of the “terms” of the prompt, but to spark something else, maybe, that the writer hadn’t considered, but now realizes must be grappled with.

What I love, as a teacher, is reading how, say, 15 different students in a workshop will take the same prompt and interpret it in 15 absolutely unique and different ways. This is exciting. It’s a way of seeing what your flood subjects are, what your inclinations are––syntactically, in terms of diction, sound, and so forth––and perhaps especially in terms of subject matter––what you can’t keep your mind off of, and how it pushes and rises up through any and all attempts to impede it with an assignment or directive. I love the pushback as much as the amazing ability of poets to hit those curveballs way out of the park, and in such surprising and moving ways.

So here the notebook pages for the poem that eventually became “Deciduous”:

![]()

and here is the poem itself, forthcoming in Literary Imagination:

Deciduous

M. virginiana

Stars, testicles, things that fall,

the labial silks of this June-spiked bloom

plucked when still a soft reptilian ovum

among elongated castanets of emerald leaves

& set afloat in a wide-mouthed bowl

of water now verdigris with rotting stem,

one nether tepal now flaccidly unfolding

to tongue the tabletop, a fun-house

inflated waterslide of plush disorder,

across which exposed carpels, already unhitched,

lie scattered like pixie matchsticks

or victims of an arctic accident, seen from the air,

genus older even than the bees, bisexual,

surviving ages of ice & continental drift

to perfume this summer room with death.

The COVID poems for my UVA alumni group have resumed for the autumn! It’s a way of connecting just one special community of writers; I’m honored also to have been able to come up with some prompts for Volume readers. In doing so, I’ve tried to think about your journal and its aesthetic (you’ll note the “requirement” to use the word “volume” in one of the prompts, and to make sure they know what a fantastic title it is for a journal, given all of its meanings). The three are crafted to invite readers of poems to engage with what they’re reading or have read (what better “obstruction” than a writer one loves?), but also with what they’re experiencing as they move through the world, in all of its voluminous luminosity, danger, and complexity.

–– I’m curious to know, how are you adjusting to the new parameters of distance and in-person learning and how has your experience as a teacher shifted––if at all? When I think of a Lisa Russ Spaar workshop, I think of the tangible sense of community you are able to create in a classroom, not only through an atmosphere of mutual respect and understanding, but also through gestures like the passing of your infamous candy bowl, which makes the rounds each class. Does distance learning do away with the sense of ritual that tethers so many of us to our creative cohorts?

Ah, the candy bowl! I made a trip into my UVA office earlier today, to fetch some books I need for teaching remotely at home, and couldn’t resist taking a Krackle bar from the bowl’s lonely well. But, to answer your question, the initial shift to remote learning last spring was very hard. I began teaching as a graduate student in 1981, so I’ve been at it for a while now, almost 40 years, and I feed off the energy and synergy created in a classroom in which people are actually gathered together in person. There’s an electricity that’s created, an accountable and very “real” sense of community. I found the removal to remote, virtual modalities deranging at times––at first. I’m getting better at it and––although between my classes and my many administrative meetings I must be Zooming at least 2 or 3 times a day; often for lengthy periods––my Zoom skills remain limited….

This semester UVA is offering both in-person and virtual options for teaching and taking classes. The graduate students began last week (in-person and/or online) and the undergrads commence next week. The students who are coming back in person are starting to move in––lots of New Jersey license plates and U-Hauls along McCormick Road this afternoon. You and I are conducting this interview in early September; it will be interesting to see where we are by the time Issue 2 of Volume appears. Well––and moving in the right direction, one hopes: in our own lives, in our institutions, our country.

I’m teaching a course I’ve taught in many iterations since about 2006: The Poetics of Ecstasy. It’s a course I love to teach, and it is a very haptic experience––the enchanted candy bowl, sure, but also one year, a student performed a Sufi dance for us; two years ago, we ended the class by pushing back the desks and dancing to Aretha and Stevie Wonder. So when I contemplated teaching this particular course online, I felt a kind of grief at the prospect. But the in-person alternative offered by my school––trying to talk about ecstasy and poetry through a face mask, shouting across a chemistry auditorium to 17 masked and distanced graduate students––was also dispiriting. So far, this term (we’ve met twice), we’re managing to have lively discussions, and it’s working because the students themselves bring so much to the table. I feel lucky to be working with them, even if I can’t pass them a Snickers bar or give a hug. You will also recall the annual big fall poetry party––sushi, cider, and other edibles and potables––and we obviously can’t do that kind of large group gathering this year. Our visitors are all coming virtually. That’s a loss as well. Things are changing, they must, and I’ve been so impressed by the ways our poets and prosers have adapted, and not just adapted but made possible new ways of interacting. Lots of distanced outdoor hiking, for instance, and porch music and readings.

–– You have a freshly published anthology with Persea Books entitled More Truly and More Strange: 100 Contemporary American Self Portrait Poems––with, as you noted, Sylvia Plath’s self-portrait on the cover. What was it like dedicating considerable time and intention to the reading, absorbing and curating of so many self-portrait poems? I’m imagining such an editorial undertaking would land me in a hall of mirrors.

Haha, yes, a hall of mirrors. Yes! In fact, there’s a whole section of the book called “Mirrors.” And the first poem in the book is Plath’s “Mirror.” The thing about anthologizing is that at first it’s so much fun, like planning a party––let me put Emily Dickinson, Rumi, Robert Pinsky, Hayden Caruth, and Emily Yaremchuk at the same table and see what happens!––but by the time one is slogging through permissions gathering (and check-writing) it feels more like wedding planning.

As I think you know, I’ve been interested in self-portraiture for a long time, and over the past ten years have taught workshops focusing on self-portraiture and also a course examining self-portraiture in visual art and poetry. As has been the case with many of my edited anthologies––All That Mighty Heart: London Poems, for example, or Monticello in Mind: 50 Contemporary Poems on Jefferson––these books have grown out of my teaching. That is, I’d put together course packets of poetry on the topic at hand since I was always unable to find extant anthologies diverse enough for my purposes, and eventually these became substantial enough for me to realize that, yes, there really is a need and a subject here. A “so what?” about the subject, whether it is insomnia or cities or a very complex founder of the United States (and the university I attended and where I now teach).

So this self-portrait anthology began as the course packet for those self-portrait classes, and I’m excited about its variety––demographically, aesthetically, with a significant range of experimentation and conception. Just a handful of poets in the book––Chen Chen, Natasha Trethewey, Joan Naviyuk Kane, Nick Flynn, Jorie Graham, Tarfia Faizullah, Ted Berrigan, Robert Creely, Miller Oberman––will give you a sense of the richness and variety associated with the self-portrait poem. We’re living a post-selfie world; even before the pandemic, so many aspects of the self were being performed, created, what have you, in virtual ways that can often inure us to the self-portrait’s craft, power, even magic.

I focused on American poets because identity is so crucial to our nation, the root of its strength and its roil, and the only thing I regret is that because the introduction and poems went to press before the pandemic hit, the ways in which this current global plague has italicized systemic American issues of race and injustice and has posed a challenge to our collective and individual notions of selfhood aren’t overtly represented in the collection (though there is a section about the self and illness, and plenty of poems about selves vexed and shaped by issues of race and social injustice). To address this concern of mine, I published an essay about the pandemic and the self that appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books on September 8th, the publication date for More Truly and More Strange. Every time I finish editing an anthology, I say, “Never again! Too much work,” but that tendency of mine to want to bring poets together already has me thinking, “What’s next?” Meanwhile, I do have a New and Selected collection, Madrigalia, coming out next fall (2021), and a “prose-something” in the fall of 2022.

–– I tremble in anticipation of an LRS “prose something”––already, I’m fascinated. What moved you to embark upon a prose journey?

This particular “prose journey” began many years ago, during which time––while I wrote and taught books of poems––I also read constantly, novels, short stories, memoirs, marveling at what writers working in various kinds of narrative, hybrid and otherwise, were able to accomplish. I’m actually a little nervous even talking about this short novel (I’ve been told by its very few readers that it IS a novel), and I think that talking about this with you is the first time I’ve publicly acknowledged that it is under contract. I’m out! I often say to my students that the opposite of poetry is not prose; plenty of poetry in the best prose, and vice versa. So… for now all I’ll say is that it explores material that I could never quite fit into my poems in just this way. Key subjects: anorexia, adolescence, orphans, hospitalization, amnesia, unrest in the 1970s, adult desire, place, the culture of work across generations of immigrants and drifters… sounds kind of boring, put this way. One hopes it adds up to more than that!

–– It actually seems impossible that a novel containing such elements could ever be boring, particularly when rendered with such a strong and uncanny eye! But, on the note of adding up to something… the making of identity, as you point out in your LARB article, is, at least in our culture, largely tied to “presenting one’s self to the public.” Self is also tied, inextricably, I think, to body. On social media, we build a sort of proxy body of self-approved content manufactured by the self, featuring the self or pertaining, however abstractly, to the self. It strikes me that poems, too, are a way of molding a proxy body––the voice on the page is physical, as “real” as the person who reads it. Like social media, its meaning is only made, only perpetuated by sharing––but a poem has a different set of requirements. To "consume" a poem, one must not only look and think, but read, and in that act of reading, one shares a voice, shares a “body” with someone else. In times like these, is that the essential magic of the poem? The ability for meaning to vault between multiple people, multiple selves, relying always on that multiplicity––an antidote to singularity?

I love what you’re suggesting here, that poetry––a special kind of language that we go to, to express or discover what can’t be said––“bodies forth” from subjective realms (desire, loss, grief, longing, anomie, duende, god hunger, all more or less “virtual” states) in part by means of the body (what Blake in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell called “the prison of the senses five”––the physical, “verifiable” world of sight, sound, smell, touch, taste). Implicit in this experience is figurative intelligence (metaphor < L metaphora to transfer; < Gk meta- & -phore “along with” “a thing or part bearing something”). In the move from abstract to figurative, unsayable oneness to post-lapsarian consciousness, poetry bears the weight of multiple realities, multiple worlds, and creates, through “voice” and “reading” the kind of “antidote to singularity” you mention above.

Poems as proxy bodies: yes! It seems to me that in building the horizontal structures of lines and the vertical structures of stanzas or strophes or blocks or columns, or scattering phrases across a page, a poem is using its segments, its joints, the contours of its syntax, the ripplings of its diction, the movements of its hinges, its wrists and elbows and ankles and knees, to dramatize living movement and rest, action and quiet, that’s every bit the same as what bodies do. Poems have pulses. Poems have respiration. Their rhythms, auditory, visual, even tactile, are the same as our rhythms. There are the ones that are tight and rigid and muscle-bound. There are the ones that are soft and uncoordinated. There are the ones that come and go, ebb and flow, in ways that make us sit up, pay attention, and tingle. If the pleasures of good poems are physical pleasures, as I really feel they are, then it follows that the physical pleasures (or pains or sensations) of poems are simply an extension or an externalization of our own physical pleasures or pains or sensations. Or think of what happens in lovemaking, the play of ebbing, flowing––the responsiveness and reciprocity. That’s one body to another, and a poem, or a good one, does the same, doesn’t it?

Well, Emily, I have to say at the start that you––your poems, your engagements with language, your imagination––continue to be an inspiration to me, even though it’s been a few years since we worked together at UVA when you were an undergraduate in our poetry honors program, the Area Program in Poetry Writing (APPW). I hope, too, that you and yours are keeping well.

One thing I’ve valued in the past few months is hearing about new projects and adventures, like the formation of Volume, for example, which are community-building and forward-looking at a time that can feel so stalled and horizon-less for many. At a time not only of plague-related and racial roil, but also in which some of the high-end publishing organizations are taking huge hits, the start of a fresh new venue for voices gives me hope. Even joy. “Volume” is a great title for a journal, by the way. It works on so many levels––not only the obvious denotation of a publication, but also in terms of physics (capacity, mass, heft, substance) and also sound––a sense of voices being heard in a range of pitches.

Because I direct two programs (both our MFA program and the APPW mentioned before) and serve on university committees, as well as teach classes at my university, I really didn’t get the “break” that sometimes happens for academics in the summer months. With my cohort of administrators, I just Zoomed on through May, June, July, and August, attempting to come up, collectively and individually, with ways to continue to teach higher education, whether in-person, online, or in some hybrid form, in a meaningful way. As someone said, it’s like flying an airplane while trying to build it.

Nonetheless, I have managed this past month (August) to read a few books for pleasure and to write some poems, essays, and reviews. One thing I did, at the request of some of the APPW poetry alumni last March, is to send out bi-weekly poetry prompts to the 180-some graduates (and current students) of the APPW. It was a way, not only for actively practicing poets, but perhaps especially for doctors, accountants, lawyers, mothers and fathers and other alumni of the program whose lives don’t ordinarily allow time for writing, people who suddenly found themselves working at their kitchen tables and with a different kind of time on their hands––to return to the making of poems. We did this from March through July and the result, collectively, is an extraordinarily moving, shared account of life and language in the time of pandemic. We took a hiatus in August, but I expect we’ll resume this fall. Connecting again with students from nearly twenty years ago, as well as those just admitted to the program, was incredibly sustaining for me during the first five months of the COVID pandemic. It reminded me why all the Zooming and other onerous challenges of trying to teach virtually––in a way that mattered––was worth it.

As a footnote: I’ll add that I have two new grandbabies––my first grandchildren––each conceived before the pandemic really hit, both due before the end of 2020. Not twins––different sets of parents. It’s a complicated time to start a family, but as the poet Charles Wright, a friend and former colleague, quipped when I told him the news: “It always is, Lisa, it always is.” Anticipating the arrival of these two new humans has been a source of hope during this hard time.

–– The poetry prompts you mention were also a pre-pandemic mainstay of your work within UVA's poetry program. Reading the three prompts you generously created for Volume, it strikes me that they are perhaps a means of “hoodwinking” poets into writing differently––of surprising them into remembering that language is always also a game and puzzle. I'm curious: do you have any specific criteria in mind, when devising a prompt? And how would you describe the place that prompts occupy in your own writing life? Are they a regular part of your practice, or are they more a tool to ease feelings of stuck-ness, of writer’s block?

I’m glad and grateful to have this opportunity to think about the genesis of “obstructions” or prompts in my own writing praxis and in my teaching. (Have you seen the Lars Von Trier movie The Five Obstructions, by the way? It’s very much a movie for poets, and for touting the ways in which art loves limits, and transcends them).

I think the beginnings of the value of being pitched something to resist as I write goes back to graduate school, when I was teaching and working a couple of other jobs while also trying to write poems. When I would get stuck on a given poem, or was stalled in a spell of writer’s block, I’d ask my husband to give me three or four randomly chosen words, and I’d use them to start a poem, looking up definitions, etymologies. In fact, I’m very much a word person, and often, most of the time, in fact, my poems begin with words that catch my interest (a word is of course itself a kind of poem, full of story, history, sonic rooms and eddies). If no one was around to pitch me words, I’d close my eyes and point randomly in the dictionary to find them (I have dictionaries in most of the rooms in my house––real ones, with letter tabs and illustrations). I still work this way, and I’ll try to insert a screen shot later of a page or two from my notebooks, where I start listing words or even little drawings on the verso (left page in a bi-fold notebook) and then start building the poem on the recto page, where at a certain point I move to the computer for finishing the draft and revising.

I use prompts with emerging and advanced students. For the former, it often helps an incipient poet by providing something with which to begin, rather than trying to conjure a poem out of nowhere (or with a break-up or Jesus). With advanced students, who are beginning to know their way around their own poems, it often forces the writer out of their comfort zone. Having something to bump up against, to try to work into a piece or, finally, resist, almost always yields not the “answer” to the assignment, but the poem the poet NEEDS to write. And that’s always the point of the prompts: not to fulfill all (or any) of the “terms” of the prompt, but to spark something else, maybe, that the writer hadn’t considered, but now realizes must be grappled with.

What I love, as a teacher, is reading how, say, 15 different students in a workshop will take the same prompt and interpret it in 15 absolutely unique and different ways. This is exciting. It’s a way of seeing what your flood subjects are, what your inclinations are––syntactically, in terms of diction, sound, and so forth––and perhaps especially in terms of subject matter––what you can’t keep your mind off of, and how it pushes and rises up through any and all attempts to impede it with an assignment or directive. I love the pushback as much as the amazing ability of poets to hit those curveballs way out of the park, and in such surprising and moving ways.

So here the notebook pages for the poem that eventually became “Deciduous”:

and here is the poem itself, forthcoming in Literary Imagination:

Deciduous

M. virginiana

Stars, testicles, things that fall,

the labial silks of this June-spiked bloom

plucked when still a soft reptilian ovum

among elongated castanets of emerald leaves

& set afloat in a wide-mouthed bowl

of water now verdigris with rotting stem,

one nether tepal now flaccidly unfolding

to tongue the tabletop, a fun-house

inflated waterslide of plush disorder,

across which exposed carpels, already unhitched,

lie scattered like pixie matchsticks

or victims of an arctic accident, seen from the air,

genus older even than the bees, bisexual,

surviving ages of ice & continental drift

to perfume this summer room with death.

The COVID poems for my UVA alumni group have resumed for the autumn! It’s a way of connecting just one special community of writers; I’m honored also to have been able to come up with some prompts for Volume readers. In doing so, I’ve tried to think about your journal and its aesthetic (you’ll note the “requirement” to use the word “volume” in one of the prompts, and to make sure they know what a fantastic title it is for a journal, given all of its meanings). The three are crafted to invite readers of poems to engage with what they’re reading or have read (what better “obstruction” than a writer one loves?), but also with what they’re experiencing as they move through the world, in all of its voluminous luminosity, danger, and complexity.

–– I’m curious to know, how are you adjusting to the new parameters of distance and in-person learning and how has your experience as a teacher shifted––if at all? When I think of a Lisa Russ Spaar workshop, I think of the tangible sense of community you are able to create in a classroom, not only through an atmosphere of mutual respect and understanding, but also through gestures like the passing of your infamous candy bowl, which makes the rounds each class. Does distance learning do away with the sense of ritual that tethers so many of us to our creative cohorts?

Ah, the candy bowl! I made a trip into my UVA office earlier today, to fetch some books I need for teaching remotely at home, and couldn’t resist taking a Krackle bar from the bowl’s lonely well. But, to answer your question, the initial shift to remote learning last spring was very hard. I began teaching as a graduate student in 1981, so I’ve been at it for a while now, almost 40 years, and I feed off the energy and synergy created in a classroom in which people are actually gathered together in person. There’s an electricity that’s created, an accountable and very “real” sense of community. I found the removal to remote, virtual modalities deranging at times––at first. I’m getting better at it and––although between my classes and my many administrative meetings I must be Zooming at least 2 or 3 times a day; often for lengthy periods––my Zoom skills remain limited….

This semester UVA is offering both in-person and virtual options for teaching and taking classes. The graduate students began last week (in-person and/or online) and the undergrads commence next week. The students who are coming back in person are starting to move in––lots of New Jersey license plates and U-Hauls along McCormick Road this afternoon. You and I are conducting this interview in early September; it will be interesting to see where we are by the time Issue 2 of Volume appears. Well––and moving in the right direction, one hopes: in our own lives, in our institutions, our country.

I’m teaching a course I’ve taught in many iterations since about 2006: The Poetics of Ecstasy. It’s a course I love to teach, and it is a very haptic experience––the enchanted candy bowl, sure, but also one year, a student performed a Sufi dance for us; two years ago, we ended the class by pushing back the desks and dancing to Aretha and Stevie Wonder. So when I contemplated teaching this particular course online, I felt a kind of grief at the prospect. But the in-person alternative offered by my school––trying to talk about ecstasy and poetry through a face mask, shouting across a chemistry auditorium to 17 masked and distanced graduate students––was also dispiriting. So far, this term (we’ve met twice), we’re managing to have lively discussions, and it’s working because the students themselves bring so much to the table. I feel lucky to be working with them, even if I can’t pass them a Snickers bar or give a hug. You will also recall the annual big fall poetry party––sushi, cider, and other edibles and potables––and we obviously can’t do that kind of large group gathering this year. Our visitors are all coming virtually. That’s a loss as well. Things are changing, they must, and I’ve been so impressed by the ways our poets and prosers have adapted, and not just adapted but made possible new ways of interacting. Lots of distanced outdoor hiking, for instance, and porch music and readings.

–– You have a freshly published anthology with Persea Books entitled More Truly and More Strange: 100 Contemporary American Self Portrait Poems––with, as you noted, Sylvia Plath’s self-portrait on the cover. What was it like dedicating considerable time and intention to the reading, absorbing and curating of so many self-portrait poems? I’m imagining such an editorial undertaking would land me in a hall of mirrors.

Haha, yes, a hall of mirrors. Yes! In fact, there’s a whole section of the book called “Mirrors.” And the first poem in the book is Plath’s “Mirror.” The thing about anthologizing is that at first it’s so much fun, like planning a party––let me put Emily Dickinson, Rumi, Robert Pinsky, Hayden Caruth, and Emily Yaremchuk at the same table and see what happens!––but by the time one is slogging through permissions gathering (and check-writing) it feels more like wedding planning.

As I think you know, I’ve been interested in self-portraiture for a long time, and over the past ten years have taught workshops focusing on self-portraiture and also a course examining self-portraiture in visual art and poetry. As has been the case with many of my edited anthologies––All That Mighty Heart: London Poems, for example, or Monticello in Mind: 50 Contemporary Poems on Jefferson––these books have grown out of my teaching. That is, I’d put together course packets of poetry on the topic at hand since I was always unable to find extant anthologies diverse enough for my purposes, and eventually these became substantial enough for me to realize that, yes, there really is a need and a subject here. A “so what?” about the subject, whether it is insomnia or cities or a very complex founder of the United States (and the university I attended and where I now teach).

So this self-portrait anthology began as the course packet for those self-portrait classes, and I’m excited about its variety––demographically, aesthetically, with a significant range of experimentation and conception. Just a handful of poets in the book––Chen Chen, Natasha Trethewey, Joan Naviyuk Kane, Nick Flynn, Jorie Graham, Tarfia Faizullah, Ted Berrigan, Robert Creely, Miller Oberman––will give you a sense of the richness and variety associated with the self-portrait poem. We’re living a post-selfie world; even before the pandemic, so many aspects of the self were being performed, created, what have you, in virtual ways that can often inure us to the self-portrait’s craft, power, even magic.

I focused on American poets because identity is so crucial to our nation, the root of its strength and its roil, and the only thing I regret is that because the introduction and poems went to press before the pandemic hit, the ways in which this current global plague has italicized systemic American issues of race and injustice and has posed a challenge to our collective and individual notions of selfhood aren’t overtly represented in the collection (though there is a section about the self and illness, and plenty of poems about selves vexed and shaped by issues of race and social injustice). To address this concern of mine, I published an essay about the pandemic and the self that appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books on September 8th, the publication date for More Truly and More Strange. Every time I finish editing an anthology, I say, “Never again! Too much work,” but that tendency of mine to want to bring poets together already has me thinking, “What’s next?” Meanwhile, I do have a New and Selected collection, Madrigalia, coming out next fall (2021), and a “prose-something” in the fall of 2022.

–– I tremble in anticipation of an LRS “prose something”––already, I’m fascinated. What moved you to embark upon a prose journey?

This particular “prose journey” began many years ago, during which time––while I wrote and taught books of poems––I also read constantly, novels, short stories, memoirs, marveling at what writers working in various kinds of narrative, hybrid and otherwise, were able to accomplish. I’m actually a little nervous even talking about this short novel (I’ve been told by its very few readers that it IS a novel), and I think that talking about this with you is the first time I’ve publicly acknowledged that it is under contract. I’m out! I often say to my students that the opposite of poetry is not prose; plenty of poetry in the best prose, and vice versa. So… for now all I’ll say is that it explores material that I could never quite fit into my poems in just this way. Key subjects: anorexia, adolescence, orphans, hospitalization, amnesia, unrest in the 1970s, adult desire, place, the culture of work across generations of immigrants and drifters… sounds kind of boring, put this way. One hopes it adds up to more than that!

–– It actually seems impossible that a novel containing such elements could ever be boring, particularly when rendered with such a strong and uncanny eye! But, on the note of adding up to something… the making of identity, as you point out in your LARB article, is, at least in our culture, largely tied to “presenting one’s self to the public.” Self is also tied, inextricably, I think, to body. On social media, we build a sort of proxy body of self-approved content manufactured by the self, featuring the self or pertaining, however abstractly, to the self. It strikes me that poems, too, are a way of molding a proxy body––the voice on the page is physical, as “real” as the person who reads it. Like social media, its meaning is only made, only perpetuated by sharing––but a poem has a different set of requirements. To "consume" a poem, one must not only look and think, but read, and in that act of reading, one shares a voice, shares a “body” with someone else. In times like these, is that the essential magic of the poem? The ability for meaning to vault between multiple people, multiple selves, relying always on that multiplicity––an antidote to singularity?

I love what you’re suggesting here, that poetry––a special kind of language that we go to, to express or discover what can’t be said––“bodies forth” from subjective realms (desire, loss, grief, longing, anomie, duende, god hunger, all more or less “virtual” states) in part by means of the body (what Blake in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell called “the prison of the senses five”––the physical, “verifiable” world of sight, sound, smell, touch, taste). Implicit in this experience is figurative intelligence (metaphor < L metaphora to transfer; < Gk meta- & -phore “along with” “a thing or part bearing something”). In the move from abstract to figurative, unsayable oneness to post-lapsarian consciousness, poetry bears the weight of multiple realities, multiple worlds, and creates, through “voice” and “reading” the kind of “antidote to singularity” you mention above.

Poems as proxy bodies: yes! It seems to me that in building the horizontal structures of lines and the vertical structures of stanzas or strophes or blocks or columns, or scattering phrases across a page, a poem is using its segments, its joints, the contours of its syntax, the ripplings of its diction, the movements of its hinges, its wrists and elbows and ankles and knees, to dramatize living movement and rest, action and quiet, that’s every bit the same as what bodies do. Poems have pulses. Poems have respiration. Their rhythms, auditory, visual, even tactile, are the same as our rhythms. There are the ones that are tight and rigid and muscle-bound. There are the ones that are soft and uncoordinated. There are the ones that come and go, ebb and flow, in ways that make us sit up, pay attention, and tingle. If the pleasures of good poems are physical pleasures, as I really feel they are, then it follows that the physical pleasures (or pains or sensations) of poems are simply an extension or an externalization of our own physical pleasures or pains or sensations. Or think of what happens in lovemaking, the play of ebbing, flowing––the responsiveness and reciprocity. That’s one body to another, and a poem, or a good one, does the same, doesn’t it?

Lisa Russ Spaar was interviewed by Emily Yaremchuk, via email, in August 2020.

©2026 Volume Poetry