The following is an excerpt from Hans Ulrich Obrist’s interview with Seba Calfuqueo for Conversations in Chile (D21 Editore/KMEC Books), forthcoming in the spring.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

How did you come to art, or did it come to you?

Seba Calfuqueo

It was my high school art teacher, Johanna Berríos, who inspired me a lot. I’m here making art because Johanna taught me to question everything in the world, and because she believed in me. I decided in my work to provoke and question experiences from my own life, things that I do not want otres (other people) to endure, like how I was bullied at my boys-only high school. Although long hair is traditional for Mapuche men, it has become associated with the feminine, and I was forced to deny the feminization of my body and to cut my hair.

That experience and many others made me want to generate critical work that addresses how social structures continue to define and limit our lives. In Chile, the society where I live, to be Indigenous and to be queer is not easy, but because of Johanna, I decided to enter the art world, a place that I still feel like I’ve infiltrated. It is very classist and very white. For me, being part of that world is a revenge—maybe revenge is not the best word—but there is a possibility in this world to have a voice. She was an incredible teacher and opened my mind.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

I always ask artists where their catalogue raisonné begins. I’m curious what you consider your very first work.

Seba Calfuqueo

It would probably be a performance piece from 2013, You Will Never Be a Weye. Although Mapuche people make up several different communities and territories across Chile and Argentina, the historical record doesn’t include our voices, offering instead interpretations by others of the symbols that form our identity and our culture. I use the machi weye and other Mapuche figures in my work not only to reference my own identity but also as a way to break apart the gender binary that has been imposed on us by colonialism. For a long time, the machi weye was a taboo subject, something only acknowledged in recent years.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Can you tell me about the machi weye?

Seba Calfuqueo

An important figure, the machi weye functions as a community healer and moves between genders. The word weye was first recorded by the Friar Luis de Valdivia in 1606 as “fag, sodomite, heinous, and devil invoker” and weyetun as “the act of sodomy.” Friar Félix José de Augusta translated kangechias “the other,” and much more recently, María Catrileo translated antü kuram as “the egg without an embryo.” There are other Western interpretations of Mapuche concepts of gender like the phrase alka domo (literally, “rooster woman”), which was translated by the Spanish Jesuit priest Andrés Febres as “man-woman.” Unlike Spanish, Mapudungun does not differentiate the gender of nouns, except for some nouns like alka (rooster), distinguished from achawall (hen). Alka domo has come to mean “hermaphrodite” or “tomboy.”

Hans Ulrich Obrist

You did a performance in 2017 called Alka domo.

Seba Calfuqueo

I wanted to resist the processes that violate us with exclusion and that are still being carried out in Abya Yala and Chile. So, I decided to use the toqui (war leader) Caupolicán (d. 1558) to question the values of colonial and patriarchal masculinity. Every student in Chile reads La araucana and knows about Caupolicán. My intention was to create a dialogue between his masculine feats and my own body. I wore different color high heels that corresponded to the six colors of the LGBTQI+ flag—red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet—and carried a hollow log of coihue on my shoulder. For the final scene I dressed completely in black, which clashed with my “violet” heels. People recognized my reference to Caupolicán and called out his name, but when they realized that the log I was carrying was hollow, there was a wave of homophobic and violent comments. The word ahuecar (to hollow out) appears in the video as a way to unlearn the symbolic value assigned to masculinity and virility because the word hueco (hollow or hole) is used in Chile as a pejorative against effeminate men; it was used against me time and time again when I was a teenager.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Were you still in the all-boys high school when you became active in social movements in Santiago?

Seba Calfuqueo

Yes, I began experimenting with dismantling gender when the tribus urbanas (urban subculture groups) exploded in Chile around 2005, a phenomenon that, by visually experimenting with their bodies, challenged the ways we distinguish feminine from masculine. A year later I participated in the student revolution in Chile, led by young people who called themselves pokemones. It wasn’t until then that I really understood that my body and my voice could be a political act, one that challenged the norms that had hurt me for so many years. I came to understand my body as a political space, a site to assert my existence and to be visible.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

You studied at the Facultad de Artes at the Universidad de Chile.

Seba Calfuqueo

Yes, but I was taught almost entirely by male professors who didn’t give room to other, non-Western ways of approaching the world. Printmaking was an important part of my first two years, but, after a while, I started to realize printmaking was limiting and incompatible with a de-colonial way of thinking. [...] I shifted to studying things like ceramics, installation, and performance. Francisco Brugnoli’s experimental workshop helped me to free myself from the patriarchal and colonialist legacy of the Universidad de Chile. When I assisted Jesús Román, she taught me to think from a visual perspective. And in the ceramics workshop of my professor Cecilia Flores, I was able to leave behind the two-dimensional format and move into a three-dimensional one.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

It’s interesting that making ceramics opened up a kind of freedom for you.

Seba Calfuqueo

I’m fascinated by the relationship between ceramic objects and the body, both in terms of their dimensions and scale and especially the relationship between the person who interacts with the object and the object itself. The effect of the object’s enamel distorts and fools the spectator’s senses, covering a material that isn’t aesthetically beautiful when raw. I’ve been exploring reproduction, copying existing pieces and watching their symbolic value mutate with each new intervention.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Many of your performances use your body as a tool.

Seba Calfuqueo

Yes, my performances have been key to my understanding that you can mark the space you are associated with—and the place where you belong in the world—through corporeality. In the staging of these performances, I have come to realize that the other senses—sight, smell, touch, hearing—can also take on an energetic, spiritual role.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

I know that you read a lot of poetry and Mapuche poets are especially important to you.

Seba Calfuqueo

The Mapuche have not had the privilege of inhabiting a single language, so having a written record of our traditions feels very political to me. Elicura Chihuailaf is now translated from Mapudungun into Spanish and English and he translates other poets from Spanish into Mapudugun. His work is super experimental, using different typographical devices and rotational axes. And I have a special connection with Daniela Catrileo, whose latest book, Piñen, builds a narrative of the Mapuche diaspora. She articulates a nonbinary aesthetic within a Mapuche space, which is very powerful. I always keep her poems and reflections close to me. In my community it is very common to pass down stories; a grandfather would explain the beginning of the world to us.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

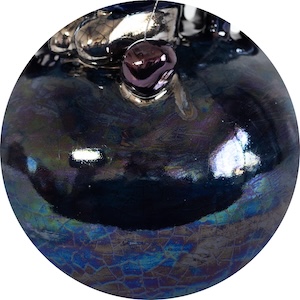

I saw in Mexico City at Zona Maco for the first time your magical ceramic sculptures. Can you tell me about them?

Seba Calfuqueo

The series of pieces that make up Imagen país are small monuments in honor of the Mapuche people's crafts, art, and creative expression from various disciplines that make up their knowledge. The pieces are small objects made of ceramic glazed with a low-temperature blue with luster of various types, a ceramic technique that simulates the relective, mirror-like quality of metal. Each piece is a way of valuing the work of creators who resist, despite colonization.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

How did you come to art, or did it come to you?

Seba Calfuqueo

It was my high school art teacher, Johanna Berríos, who inspired me a lot. I’m here making art because Johanna taught me to question everything in the world, and because she believed in me. I decided in my work to provoke and question experiences from my own life, things that I do not want otres (other people) to endure, like how I was bullied at my boys-only high school. Although long hair is traditional for Mapuche men, it has become associated with the feminine, and I was forced to deny the feminization of my body and to cut my hair.

That experience and many others made me want to generate critical work that addresses how social structures continue to define and limit our lives. In Chile, the society where I live, to be Indigenous and to be queer is not easy, but because of Johanna, I decided to enter the art world, a place that I still feel like I’ve infiltrated. It is very classist and very white. For me, being part of that world is a revenge—maybe revenge is not the best word—but there is a possibility in this world to have a voice. She was an incredible teacher and opened my mind.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

I always ask artists where their catalogue raisonné begins. I’m curious what you consider your very first work.

Seba Calfuqueo

It would probably be a performance piece from 2013, You Will Never Be a Weye. Although Mapuche people make up several different communities and territories across Chile and Argentina, the historical record doesn’t include our voices, offering instead interpretations by others of the symbols that form our identity and our culture. I use the machi weye and other Mapuche figures in my work not only to reference my own identity but also as a way to break apart the gender binary that has been imposed on us by colonialism. For a long time, the machi weye was a taboo subject, something only acknowledged in recent years.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Can you tell me about the machi weye?

Seba Calfuqueo

An important figure, the machi weye functions as a community healer and moves between genders. The word weye was first recorded by the Friar Luis de Valdivia in 1606 as “fag, sodomite, heinous, and devil invoker” and weyetun as “the act of sodomy.” Friar Félix José de Augusta translated kangechias “the other,” and much more recently, María Catrileo translated antü kuram as “the egg without an embryo.” There are other Western interpretations of Mapuche concepts of gender like the phrase alka domo (literally, “rooster woman”), which was translated by the Spanish Jesuit priest Andrés Febres as “man-woman.” Unlike Spanish, Mapudungun does not differentiate the gender of nouns, except for some nouns like alka (rooster), distinguished from achawall (hen). Alka domo has come to mean “hermaphrodite” or “tomboy.”

Hans Ulrich Obrist

You did a performance in 2017 called Alka domo.

Seba Calfuqueo

I wanted to resist the processes that violate us with exclusion and that are still being carried out in Abya Yala and Chile. So, I decided to use the toqui (war leader) Caupolicán (d. 1558) to question the values of colonial and patriarchal masculinity. Every student in Chile reads La araucana and knows about Caupolicán. My intention was to create a dialogue between his masculine feats and my own body. I wore different color high heels that corresponded to the six colors of the LGBTQI+ flag—red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet—and carried a hollow log of coihue on my shoulder. For the final scene I dressed completely in black, which clashed with my “violet” heels. People recognized my reference to Caupolicán and called out his name, but when they realized that the log I was carrying was hollow, there was a wave of homophobic and violent comments. The word ahuecar (to hollow out) appears in the video as a way to unlearn the symbolic value assigned to masculinity and virility because the word hueco (hollow or hole) is used in Chile as a pejorative against effeminate men; it was used against me time and time again when I was a teenager.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Were you still in the all-boys high school when you became active in social movements in Santiago?

Seba Calfuqueo

Yes, I began experimenting with dismantling gender when the tribus urbanas (urban subculture groups) exploded in Chile around 2005, a phenomenon that, by visually experimenting with their bodies, challenged the ways we distinguish feminine from masculine. A year later I participated in the student revolution in Chile, led by young people who called themselves pokemones. It wasn’t until then that I really understood that my body and my voice could be a political act, one that challenged the norms that had hurt me for so many years. I came to understand my body as a political space, a site to assert my existence and to be visible.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

You studied at the Facultad de Artes at the Universidad de Chile.

Seba Calfuqueo

Yes, but I was taught almost entirely by male professors who didn’t give room to other, non-Western ways of approaching the world. Printmaking was an important part of my first two years, but, after a while, I started to realize printmaking was limiting and incompatible with a de-colonial way of thinking. [...] I shifted to studying things like ceramics, installation, and performance. Francisco Brugnoli’s experimental workshop helped me to free myself from the patriarchal and colonialist legacy of the Universidad de Chile. When I assisted Jesús Román, she taught me to think from a visual perspective. And in the ceramics workshop of my professor Cecilia Flores, I was able to leave behind the two-dimensional format and move into a three-dimensional one.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

It’s interesting that making ceramics opened up a kind of freedom for you.

Seba Calfuqueo

I’m fascinated by the relationship between ceramic objects and the body, both in terms of their dimensions and scale and especially the relationship between the person who interacts with the object and the object itself. The effect of the object’s enamel distorts and fools the spectator’s senses, covering a material that isn’t aesthetically beautiful when raw. I’ve been exploring reproduction, copying existing pieces and watching their symbolic value mutate with each new intervention.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Many of your performances use your body as a tool.

Seba Calfuqueo

Yes, my performances have been key to my understanding that you can mark the space you are associated with—and the place where you belong in the world—through corporeality. In the staging of these performances, I have come to realize that the other senses—sight, smell, touch, hearing—can also take on an energetic, spiritual role.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

I know that you read a lot of poetry and Mapuche poets are especially important to you.

Seba Calfuqueo

The Mapuche have not had the privilege of inhabiting a single language, so having a written record of our traditions feels very political to me. Elicura Chihuailaf is now translated from Mapudungun into Spanish and English and he translates other poets from Spanish into Mapudugun. His work is super experimental, using different typographical devices and rotational axes. And I have a special connection with Daniela Catrileo, whose latest book, Piñen, builds a narrative of the Mapuche diaspora. She articulates a nonbinary aesthetic within a Mapuche space, which is very powerful. I always keep her poems and reflections close to me. In my community it is very common to pass down stories; a grandfather would explain the beginning of the world to us.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

I saw in Mexico City at Zona Maco for the first time your magical ceramic sculptures. Can you tell me about them?

Seba Calfuqueo

The series of pieces that make up Imagen país are small monuments in honor of the Mapuche people's crafts, art, and creative expression from various disciplines that make up their knowledge. The pieces are small objects made of ceramic glazed with a low-temperature blue with luster of various types, a ceramic technique that simulates the relective, mirror-like quality of metal. Each piece is a way of valuing the work of creators who resist, despite colonization.

Seba Calfuqueo is a Mapuche artist and activist. Part of the Mapuche collective Rangiñtulewfü and Yene Revista, Calfuqueo’s work in installation, ceramic, performance, and video investigates race, gender, and social class. Her practice proposes a decolonial view and a critical reflection of the social, cultural, and political status of the Mapuche subject in contemporary Chilean society and Latin America. Her work has been exhibited in Chile, Peru, Brazil, Mexico, United States, Germany, Spain, United Kingdom, Sweden, Switzerland, and Australia.

Hans Ulrich Obrist is a world-renowned curator and the artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries in London. Alongside his curatorial practice, Obrist has written extensively on and around contemporary art, with a particular interest in the interview format.

Hans Ulrich Obrist is a world-renowned curator and the artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries in London. Alongside his curatorial practice, Obrist has written extensively on and around contemporary art, with a particular interest in the interview format.